|

|

| www.wildfirenews.com | ARCHIVED 06-09-2003 |

|

CLIMATE CHANGE PROJECTS ALTER FORECASTSJune 09 -- CORVALLIS, OR: Computers loaded with weather data and vegetation maps can look over the past century and find the confluences of heat, dryness, and fuel that produced the Yellowstone fires of 1988 and the Tillamook burns of the 1930s. But can they accurately look far enough into the future to allow the U.S. Forest Service to budget scarce firefighting funds, target forest thinning projects and prescribed burning, or even help decide where and when to deploy fire crews and equipment? A team of Forest Service scientists is working to make it so. "Predicting this upcoming fire season is probably not as important as predicting fire seasons out two or three years," says Ronald Neilson, a bioclimatologist at the Pacific Northwest Research Station and team leader on the project. "If you had enough advance notice, you could get out and do pre-fire burning. You could pull the fuel rug out from under it." That would be a huge breakthrough in long-range wildfire forecasting, according to an AP report on Newsday.com "It's in its infancy," says Tim Brown, director of the Program for Climate, Ecosystem and Fire Applications (CEFA) at the Desert Research Institute in Reno. "It's getting very close to starting to have important value." Three years ago, the National Fire Plan began funding wildfire forecasting research. One tool is the National Wildland Fire Seasonal Outlook from NIFC. It was developed from a meeting in February of some 30 meteorologists, climatologists, and fire managers who gathered in Tucson to pool their expertise. They considered winter snowpack, moisture in dead wood, drought, fire history, spring rains, summer lightning patterns, and long-range weather forecasts. The current outlook, according to Rick Ochoa, national fire weather program manager for the BLM, calls for an above-average season, but far milder than last year's. Back in his days on a hotshot crew, Mike Fitzpatrick, intelligence coordinator for the Northwest Interagency Coordination Center in Portland, knew a crew foreman who always said the rain in June would set the season. When Fitzpatrick told that story to Paul Werth, the fire weather program manager looked through 33 years of fire history and noticed that big fire seasons came after a dry winter followed by a dry June. The system was put to the test in 2001. Forecasters spotted a lightning storm moving north through California. Typically, those storms move up the Cascades to Mount Jefferson, then head east toward the Wallowa Mountains. The climate zones showed the greatest fire potential in northeastern Oregon. So fire crews and equipment were shipped to the area before the storms hit. "We were successful in containing all but three of the 200 fires that started," Fitzpatrick recalled. For the next century, the model shows temperatures rising, causing more rain over much of the West. maps of fire regimes and fuel buildups were inserted, and two of the three resulting climate scenarios show a high potential for fire in southwestern Oregon and northern California -- particularly around Lake Tahoe. For all that forecasters can do to calculate fire potential, they still have no good way to foresee the spark that actually ignites a fire, says Neilson. "There are two components -- lightning and people -- both of which are very hard to predict."

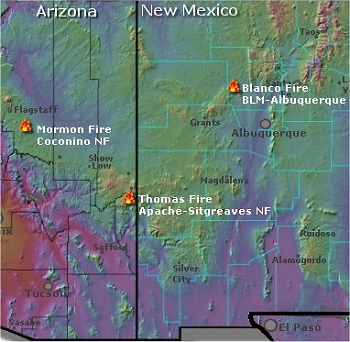

ARIZONA FIRE DOUBLES IN SIZEJUNE 09 -- ALPINE, AZ: A wildfire on the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest doubled in size yesterday, burning in steep and rocky terrain about 15 miles south of Alpine.

Four homes and ten outbuildings are threatened; an AP report in the Arizona Republic noted that the closest home is nearly a mile away. Kvale's Type 2 team is on the fire along with nine Type 1 crews, five Type 2 crews, four helicopters, three engines, a dozer, and a watertender. The fire's burning in the Blue Primitive Area, which is steep and rugged with heavy fuels. The Southwest Area Coordination Center reported 23 new fires in the region yesterday; ten were on the Coconino National Forest. The Mormon Fire southeast of Flagstaff was ignited by lightning on Friday and was reported at 300 acres this morning. It's burning in piñon and is in a confinement strategy -- aerial recon is occurring twice a day. The Blanco Fire west of San Ysidro, New Mexico, which started last Wednesday, has been contained at 640 acres. Crews are mopping up. The Dry Lakes Complex northwest of Silver City is now up to 4,675 acres, and is being managed by Rath's Fire Use team. These fires are being monitored, structure protection for historical sites is in place, and aerial monitoring is occurring.

MISSIONARY RIDGE FIRE: ONE YEAR LATERJune 08 -- DURANGO, CO: By all accounts, last year's Missionary Ridge Fire was an extraordinary fire. The drought conditions, single-digit humidity, steep and overgrown terrain, and high winds combined for the perfect setting for an extraordinary fire. "I don't think there are many firefighters around the country that our fire wouldn't have impressed," said Pauline Ellis, ranger and field manager for the Columbine District of the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management. "Once in a lifetime." Creating defensible space around homes does work, and as the Durango Herald reported, some homes were saved because of that work. One home in the Falls Creek subdivision was spared when fire-mitigation work stalled flames at the edge of the property. But a home's survival often depends on nothing more than chance.

The vortex, which Ellis says impressed even the most seasoned federal firefighters, illustrates the extreme behavior of the fire. Towering plumes of smoke -- the tallest at 44,000 feet -- collapsed, throwing heat and embers and starting spot fires a mile away. Ron Klatt, Columbine District FMO, said the plumes that normally would have dissipated in the air just fell like buildings. He recalls the surprise of fire behavior experts who told residents on June 13 that they had two or more days before the fire reached them -- and their subdivision was evacuated minutes later. Ellis watched incident management teams arrive with confidence and then leave humbled. Firefighters with 30 years of experience were continually astonished, she said. Klatt said the fire was destined to be a big one. "We didn't honestly have a chance at the Missionary Ridge Fire," he said. "There's going to be certain times and certain places where you're just not going to be successful."

UTAH'S FIRST BIG FIRE OF THE SEASON BURNING NEAR HANKSVILLEJUNE 06 -- SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH: Utah's first large wildfire of the season is burning 20 miles southwest of Hanksville in southern Utah. KSL-TV reported that firefighters are taking a slow, low-cost approach to attacking it. The Lonesome Beaver Fire started Friday evening when lightning struck a tree near the Lonesome Beaver Campground in the Henry Mountains. It's burning mostly in piñon-juniper. "The fuels are extremely dry," said BLM information officer Bert Hart. "They just haven't had a chance to recover." The Salt Lake Tribune reported that BLM managers had expected that the fire would burn itself out, but it ripped across more than 1,700 acres yesterday. Hart said flamelengths were as high as 100 feet. The remote location and rugged terrain are making it difficult for crews to reach the fire; the Henry Mountains are so remote that they were one of the last mountain ranges in the United States to be named. "Since access is so nasty, safety is the utmost factor," said Hart. "We aren't going to put people in an area that's not safe." Wind and high temperatures allowed the fire to grow rapidly on Wednesday, but it settled down some yesterday as the weather turned cooler and winds subsided. The fire's burned into two wilderness study areas, and there are a few cabins and three campgrounds in the area. Hart said the BLM is focusing on structure protection. "We're trying to keep the cost down," he said. About 200 personnel, two helicopters, and five engines are expected to be on the fire today. More information's available from BLM Utah Fire Management.

OAKLAND HILLS FIRE EXHIBIT OPENEDJune 03 -- OAKLAND, CA: As California's fire season officially opens, a stark garden portraying the danger of wildfire has also opened in the Oakland hills. The Gateway Emergency Preparedness Exhibit Center and Garden, a project designed and built by survivors of the 1991 inferno that killed 25 people and destroyed 3,000 homes, is sited not far from the flashpoint of the big fire. With a panoramic view of the hills and a pavilion representing a fire-gutted home, it stands as a reminder to keep vegetation to a minimum. "This is not a memorial -- it is educational," said Sue Piper, a fire survivor and the driving force behind the project with her husband, Gordon. On Monday, the official start of the fire season, firefighters contained the first major northern California wildfire of the year. The San Francisco Chronicle reported that it started Sunday near Tracy, burned 7,000 acres of grassland, and threatened four mobile homes. The Oakland garden and exhibit is in the middle of one of the diciest places in California's wildland/urban interface. The garden includes paths that wind among granite boulders; next to the garden is a tower of stone symbolizing the chimneys that dotted the smoldering hills on October 21, 1991. The exhibit argues that people can and should create defensible space so that fires burn less hot and less often. "We've gotten religion," Sue Piper said. "We just don't want it to happen again." "Although I conceived it in terms of the ghosts of former houses, I thought it really represented the rebuilding," said Peter Scott, who planned the pavilion. "It's really a combination of the two. It's to remind us that fires and earthquakes happen periodically. It's not like they happen once and never happen again." A nonprofit group called the Claremont Canyon Conservancy is pushing public landowners for better vegetation management in hills just north of the 1991 fire area. "On a scale of 10, they're about 1," said the conservancy's Tim Wallace, a retired professor and former state agriculture director. Claremont Canyon remains one of the hotspots of the hills, with ample fuel, lots of human activity, tough firefighting conditions, and a tight squeeze between forest and city. For more information on the Gateway exhibit, check their website at ergateway.org/site/ergateway/

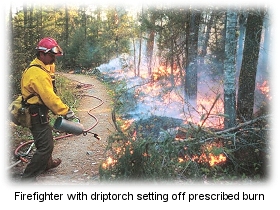

WHAT A DIFFERENCE A YEAR MAKESJUNE 02 -- SEA GULL LAKE, MN: A year ago the forest on Three Mile Island was an impenetrable tangle of downed trees and brush, a mess left behind after the massive windstorm of 1999.

Parts of the island -- after the fire -- now resemble a lunar landscape, bare rocks exposed where lush moss and brush once grew. Charred trees -- a few standing, most fallen -- are everywhere. What a difference a year and a big fire can make.

Woodpeckers, jays, warblers, and robins all returned to the island quickly after the fire, with plenty of insects around for them to eat. Seedlings are sprouting from the ash, including birch trees, raspberries, lilies, and more. Wild geraniums, their seeds dormant since the island's last major fire in 1801, are sprouting nearly everywhere. "The fire seems to have mimicked a wildfire very closely, which is what you want to see ecologically," said Allen Haney, a forest ecologist for the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point who has been conducting research on the island for more than two decades. Haney was one of a dozen forest researchers and USFS personnel who recently visited the island; they were checking to see whether the fire met both the environmental objectives and the safety objectives as it consumed timber downed by the windstorm.

The fire was designed to burn slowly, starting downwind and backing upwind. But in areas where the wind damage was severe, the fire took off much faster than expected, shooting flames 60 feet in the air and burning fast even into the wind. The fire was so hot in spots that it melted aluminum flags left by researchers to mark their study areas. That's about 1,200 degrees Fahrenheit. Still, pockets of lush green growth remain across the island. In all, about 1,000 acres on the island burned, about 85 percent. The other 15 percent will act as seed source for regrowth of the forest.

Lee Frelich, University of Minnesota forest ecologist, says cedar trees at least 600 years old and perhaps more than 1,000 years old survived the fire. Frelich has documented these as the oldest in the state. He's identified one red pine stand that is 5,000 years old, and he expects most of them to survive for centuries to come. "Other species come and go, but they are unique," Frelich said. "They have survived fire and wind in a place where nothing else can. At least not for 600 years."

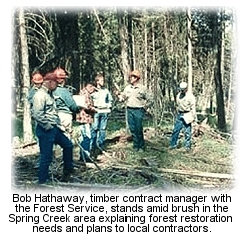

MODEL FOR FOREST RESTORATION CONTRACTS PLANNED IN BLUE MOUNTAINSJune 01 -- LA GRANDE, OR: Forest Service personnel and environmental activists are hoping that a new type of logging contract in the forests near La Grande will provide a model for restoration. La Grande District Ranger Kurt Wiedenmann is a proponent of innovative resource management contracts, including goods-for-services and stewardship contracts, new to the national forests and proposed for a restoration project near Spring Creek in the Blue Mountains.

The sale of timber at good market prices is essential for the contractors to make a profit; the La Grande Observer reported that the bid price for the Sprinkle Project will be offset by the restoration cost to the national forest. "Sprinkle is a more holistic approach to resource management," said Brett Brownscombe with the Hells Canyon Preservation Council. "It's worth looking at, and we hope the contractors will receive it favorably and get into more restoration service work instead of focusing exclusively on thinning and logging." The project was initially planned as a timber sale; then the Union County Forestry Committee became involved. "The intent of a stewardship is to involve communities and collaborate," said Brownscombe. "In the future, we want to see up-front community involvement and planning." Brownscombe and local forester John Herbst will help monitor the project, which will include logging of about 2,400 acres. The area contains a small patch of old-growth and a large number of small-diameter trees, both standing and downed; much of the area has been hit with beetle infestation. To protect the forest from fire, the smaller trees will be thinned. The monitoring committee has designated photography points to measure the progress of restoration. "The idea is to protect the old growth from fire," Brownscombe said. "The area is far more dense than it would have been. It's pretty clear in the Blue Mountains what we have left are relatively small-diameter trees, high-road density. The restoration needs are greater than just thinning, although thinning is a part of it, but so is road decommissioning, wildlife enhancement." The successful bidder on the project will remove smaller non-commercial trees and debris. Forest Service bookkeepers record the amount of restoration and deduct those costs from the bid price. Bids are expected to be awarded in early July. In areas where there are many dead and downed trees and heavy brush, the contractors must reduce the excess fuels to no more than 15 tons per acre. No trees larger than 21 inches in diameter will be taken; Hathaway estimates that between 15 and 25 tons per acre must be removed. "Leave the good trees, that's all we ask," Hathaway told the contractors. "We don't want mistletoe left."

CREWS GAINING ON TOK RIVER FIREMAY 31 -- FAIRBANKS, ALASKA: A wildfire near Tok slowed some yesterday and even weathered a thunderstorm that could have hampered firefighting efforts. The fire had burned almost 3,000 acres by yesterday evening, according to the Fairbanks News-Miner, but a two-hour thunderstorm in the early afternoon didn't generate the high winds that had driven the fire in its first two days. "They're in pretty good shape right now, as far as controlling these spot fires," said Pete Buist with the Alaska Division of Forestry. "But we're not calling them controlled." Reed's Type 2 team is assigned to the fire, which is burning in black spruce, tundra, and mixed hardwoods five miles southeast of Tok. The fire was spotted from the Tok Cutoff by a state Department of Transportation worker late Tuesday morning. On Wednesday, winds blew embers to the other side of the Tok River, which had separated the fire from Tok, a town of about 1,300 people. The largest spot fire was estimated at 50 acres and the smallest was about five acres. The fire was at first wind-driven, but it turned into a terrain-driven fire as it headed into the Tetlin Hills. "Fire moves more rapidly up slope," said Buist. "The fire still has the potential to grow and spread not only to the Tetlin Hills or the Alaska Range (to the south) but to the north towards town." A red-flag warning was issued because of the dry conditions and lightning from the thunderstorms.

VOLCANO FIRE IN HAWAII GROWS TO 4,200 ACRESMAY 31 -- VOLCANO, HAWAII: Firefighters are working to contain a rash of brushfires that have burned more than 4,000 acres on the western edge of Kilauea within Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. The Luhi fires, according to West Hawaii Today, were ignited by lava last Thursday and have picked up in recent days with dry, hot weather conditions. Two of three fires merged Wednesday and burned about 4,000 acres of unburned rainforest; the other fire burned another 235 acres. "Half of the East Rift Special Ecological Area burned, and the remainder is threatened," said Rhonda Loh, the park's vegetation specialist. Forty firefighters and four helicopters are working to contain the fire and prevent its further spread into the rain forest. A control line was established to protect three patches of lamu forests in the hairpin curves of Chain of Craters Road. The Hawaii Tribune-Herald reported that the fire was burning some of the same areas scorched by fires ignited by last year's Mother's Day lava flow. The fire, according to Jim Gale, the park's chief of interpretation, wasn't threatening any structures or visitors; the fires are burning in an open forest area dominated by uluhe fern. Last year, fires ignited by a lava on Mother's Day burned more than 3,600 acres.

|

On the ninth day of the Missionary Ridge Fire, the fire created a small tornado at Vallecito Reservoir that ripped trees from the ground and killed birds in flight. Butch Knowlton, director of emergency preparedness for La Plata County, recalls that the valley became clear as the smoke was sucked into the funnel. He believes the vortex, which momentarily halted the fire's progress, may have saved homes at the north end of the reservoir. But at the same time, the vortex wrecked cars that had been moved into a "safe zone" in the dry lakebed at the north end of the reservoir.

On the ninth day of the Missionary Ridge Fire, the fire created a small tornado at Vallecito Reservoir that ripped trees from the ground and killed birds in flight. Butch Knowlton, director of emergency preparedness for La Plata County, recalls that the valley became clear as the smoke was sucked into the funnel. He believes the vortex, which momentarily halted the fire's progress, may have saved homes at the north end of the reservoir. But at the same time, the vortex wrecked cars that had been moved into a "safe zone" in the dry lakebed at the north end of the reservoir.

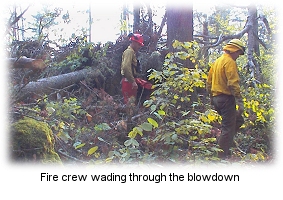

Heavy rain and straight-line winds in excess of 90 mph hit north-central and northeastern Minnesota on July 4, 1999, blowing down trees and causing severe flooding. On the Superior National Forest, 477,000 acres (more than 600 square miles) were impacted by blowdown, including one third of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW). On the Chippewa National Forest, about 12,000 feet of lakeshore was severely damaged from erosion and 6,000 acres of timber was covered with blowdown.

Heavy rain and straight-line winds in excess of 90 mph hit north-central and northeastern Minnesota on July 4, 1999, blowing down trees and causing severe flooding. On the Superior National Forest, 477,000 acres (more than 600 square miles) were impacted by blowdown, including one third of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW). On the Chippewa National Forest, about 12,000 feet of lakeshore was severely damaged from erosion and 6,000 acres of timber was covered with blowdown.

Last September, a Forest Service helicopter dropped ping-pong balls on the island. The goal was to get rid of the wind-broken trees drying wood wouldn't fuel a big wildfire ignited by lightning or careless campers. And, according to the

Last September, a Forest Service helicopter dropped ping-pong balls on the island. The goal was to get rid of the wind-broken trees drying wood wouldn't fuel a big wildfire ignited by lightning or careless campers. And, according to the  "It was a beautiful burn from our perspective," said Dennis Neitzke, Gunflint district ranger for the

"It was a beautiful burn from our perspective," said Dennis Neitzke, Gunflint district ranger for the  Roy Rich, a University of Minnesota grad student who is studying blowdown and fire effects on the forest, says it's an example of "accelerated succession." Across much of the blowdown area where there has been no fire, maple, birch, aspen, and fir are racing to take the place of downed pines. "After the fire, there were birch seeds everywhere," said Rich. "I think birch is going to be the big winner on this island after this fire."

Roy Rich, a University of Minnesota grad student who is studying blowdown and fire effects on the forest, says it's an example of "accelerated succession." Across much of the blowdown area where there has been no fire, maple, birch, aspen, and fir are racing to take the place of downed pines. "After the fire, there were birch seeds everywhere," said Rich. "I think birch is going to be the big winner on this island after this fire."

"These are multi-million-dollar contracts," Wiedenmann said. "Very serious business. We're creating jobs and meeting our resource objectives."

"These are multi-million-dollar contracts," Wiedenmann said. "Very serious business. We're creating jobs and meeting our resource objectives."